I’ve been a distance runner and nordic skier since high school. Managing blood sugar while training is a pain – hypoglycemia can be dangerous while hyperglycemia makes you feel like garbage. Any deviation from ideal glucose reduces performance, blunts recovery, and has long term health consequences. So how can you manage blood glucose during intense exercise? There’s a lot to talk about here. When should you turn off or remove your insulin pump? Should you be constantly downing granola bars and gels? How does exercise duration affect glucose? What about intensity? Does exercise mode on the pump really do anything? And what can we do after finishing a workout to prevent glucose excursions?

Fuel for Insulin on Board

Exercise dramatically and temporarily increases insulin sensitivity. That is, sensitivity to the insulin currently acting in the body. Remember that “rapid acting” insulin’s effect rises to a peak between 1 and 1.5 hours and slowly trails off. For this reason, during a 30 minute run, the most important predictor of low blood sugar is not what the pump is doing during the run, but how much insulin is in your system in the one to three hours prior to the exercise.

Short Stuff

For shorter efforts, any reductions in insulin must come before the exercise rather than during. I do most of my short casual runs first thing in the morning, and I typically train fasted and leave my pump on. I’ve found that suspending or taking off my pump for short duration exercise only results in post-exercise high blood sugars and yields no benefit in preventing hypoglycemia during less than 30 minute workouts. If training between 30 minutes and an hour, eating a granola bar or gel around 15-30 minutes in and another 45 minutes in usually works OK to prevent lows. Alternatively, taking off the pump typically prevents almost all lows during morning runs, but can lead to under-fueling.

Long Stuff

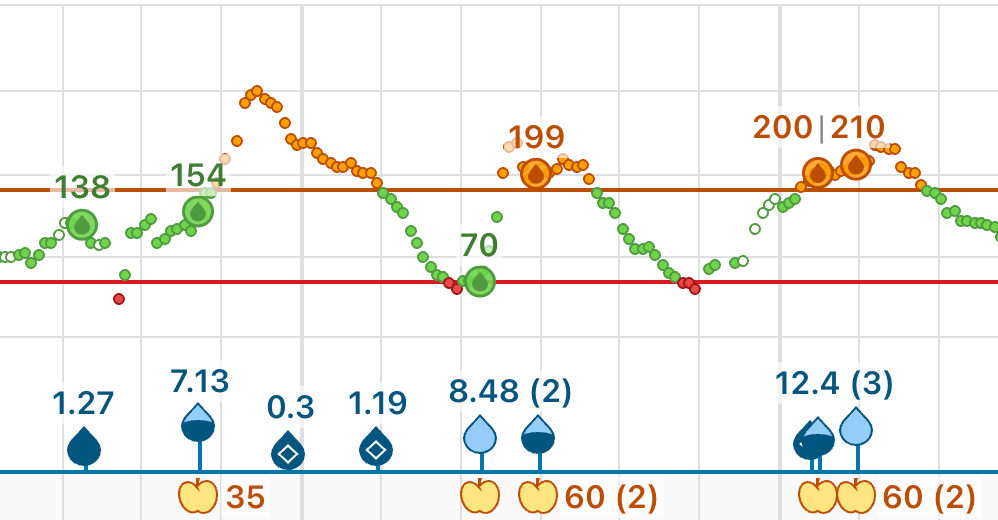

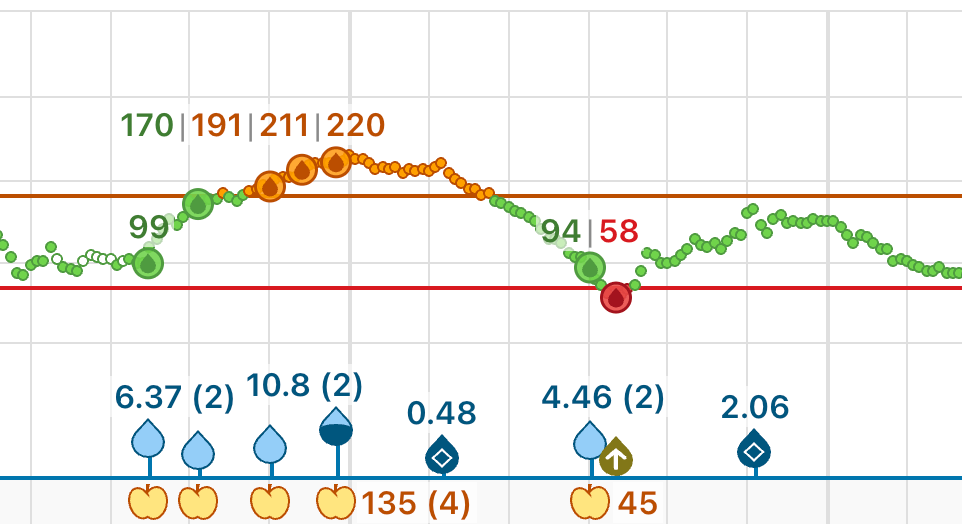

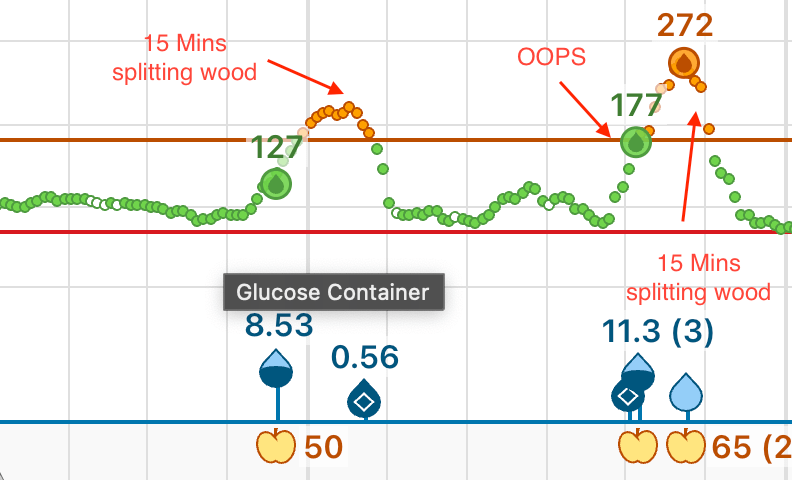

During long hard efforts like a multi-hour trail run, if I have insulin on board I need to consume tons of carbs to prevent my number from going low. One option is to disconnect the pump before and during these efforts to prevent lows. While this can work, I find my number tends to start high then either stay high or crash. To avoid starting high, I prefer to keep the same amount of insulin on board and fuel consistently starting 15 minutes before I begin my workout. That way my number doesn’t skyrocket before I start nor does it plummet in the first half an hour of work. If I keep my pump at its normal basal rate, I can eat pretty much any quantity of carbs during a sufficiently hard effort and my number rarely goes above 120. Carrying so much food can be challenging, and I’m not sure that eating ten sugary granola bars during a two hour trail run does my teeth any favors. That said, there is a shift towards high carb fueling for long duration exercise, and this approach allows type 1 diabetics to follow a high carb fueling strategy without spiking blood glucose.

Intensity

Intense, short duration exercise fails to lower my blood sugar the way longer duration cardio workouts do. For me, I rarely have an issue when lifting weights or running a track workout. For longer stuff like mountain runs and tempo runs, higher intensity typically means more insulin sensitivity, more fuel required, and a greater risk of lows. So where’s the cutoff? My best guess is that there are two factors at play – acute stress and total energy expenditure. Stress tends to make us insulin resistant. Energy expenditure causes the muscles to suck up glucose and make us insulin sensitive. Doing three sets of ten squats to failure puts a ton of stress on the body, but doesn’t actually burn that many calories. Even a brutal track workout like 12×400 or mile repeats don’t result in tons of calories burned compared to a two hour mountain run. Long slow cardio burns a ton of energy but puts relatively little stress on the body.

Fasted Training

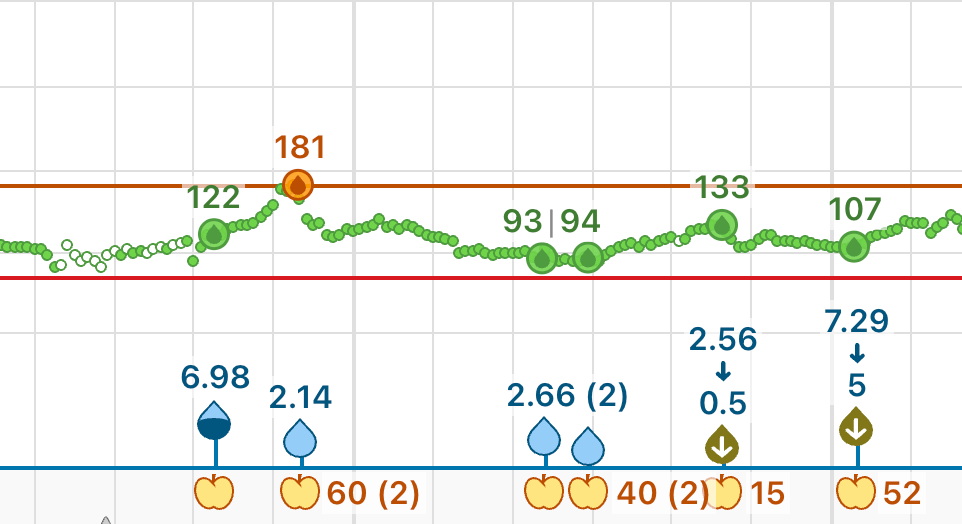

It is possible to start without much insulin on board and fuel minimally. For me, this typically means training first thing in the morning. I find that running first thing in the morning has a few benefits. First, it helps me reduce or entirely avoid the rise in glucose after waking, otherwise known as the dawn phenomenon. Since there’s minimal insulin on board when I wake up, my glucose tends not to fall as quickly. In the morning I can typically go for an hour long run without eating anything and not experience hypoglycemia. While this is ideal in terms of maintaining a stable blood sugar, the lack of fueling both limits performance and might fatigue my body unnecessarily. While it’s anecdotal, the only time I recently got an overuse injury running was when I routinely ran 13+ mile fasted morning runs.

Insulin Pump Exercise Mode

Exercise mode claims to reduce basal insulin and corrections on closed loop insulin pumps. Personally, I find it next to useless. It’s delivers way too much insulin to train without substantial fueling (in which case, I’d prefer to leave the pump in its normal setting), fails to keep my number in check when I fuel heavily, and I frequently forget to disable it after my workouts. More broadly, a one-size-fits-all exercise mode fundamentally doesn’t make sense to me. Does exercise mean a stroll around the neighborhood, going for a leisurely long run or competing in a 5k? What about a track workout, nordic skiing, or yoga? I get the sense they cater more to walks around the block than marathon training, though I find that even during a leisurely round of golf my number goes low in exercise mode. Has anybody had success using exercise mode? Maybe I’m missing something – let me know!

Post Exercise and Recovery

After finishing a workout, I find my insulin sensitivity quickly returns from hypersensitive during the run back to near normal levels. If my pump has been off, my insulin on board will be low and my number will climb quickly, especially if I eat. To counteract this, If I did take off my pump (something I’m trying to do less these days) I deliver a bolus a soon as I finish to approximately cover the missing basal during my run plus a pre-bolus for any food I’m planning to eat. I’ve found I need to increase this bolus in the morning to something like double the basal missed, likely due to dawn phenomenon and lower overall IoB.

If I kept the pump on and fueled my work, I find my post exercise numbers are much more stable. If anything, I keep an eye out for lows since I find my sensitivity stays higher than baseline thus a normal correction or basal delivery might send me low.

Conclusion

Exercising is amazing for the body and type 1 diabetes need not limit the type, intensity or duration of exercise we can engage in. While carrying 400 carbs with me on a long run can be annoying, I find that fueling my work makes me feel great, perform great, and allows me to stay in range for the duration of my effort.